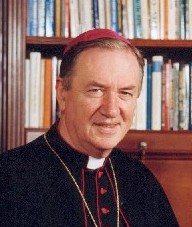

On Sunday 22nd June Bishop Joseph Duffy celebrated fifty years of ordination. Born 3 February 1934 of Edward Duffy and Brigid MacEntee, Annagose, Newbliss, Co. Monaghan. Joseph Duffy was the eldest of three boys and one girl. He was educated at St Louis Infant School, Clones, Largy N.S., Clones, and in St Macartan’s College, Monaghan, where he was a boarder for five years.

He studied for the priesthood at St Patrick’s College, Maynooth, and was ordained priest for the Diocese of Clogher on 22 June 1958. On 2 September 1979 he was ordained Bishop of Clogher

A special Mass to celebrate the occasion took place in Monaghan Cathedral on Sunday 22nd June at 3 P.M. As well as celebrating Bishop Duffy’s 5oth Anniversary the Mass also marked the occasion and sending of a large group of young people from the Diocese who will be travelling on pilgrimage to World Youth Day this summer.

A large number attended the celebration Mass and refreshments afterwards in the Hillgrove Hotel.

The priests and the people of the Diocese wishes Bishop Duffy their warmest congratulations on this wonderful occasion.

Golden Jubilee Mass: Homily by Bishop Joseph Duffy

22 June 2008

During the past week I performed a marriage liturgy for a nephew and his bride down the country. It’s a celebration that comes my way fairly seldom, but it never fails to get me thinking. What impresses me is the sheer challenge of marriage, the maturity, experience and generosity required to make it work, to make it not only to survive but to thrive and expand into family and consequent commitments. Like many of you, over the years I have seen success and failure in this area. I have watched couples grow together, I have seen initial idealism seasoned and at times wrecked by hard knocks and disappointments, I have admired the patience, the struggle for fidelity, the enormous sacrifices which marriage demands in order to take the best out of people, in order to rise above mediocrity and mere outward show.

Then I think of my own vocation to priesthood. The two vocations are, of course, very different. As a married couple your first commitment is to one another and flowing from that to your children and their many needs. For priests the circle is wider. We pledge our lives to the care of a group of people who have regular but mostly fleeting degrees of contact with us, depending more on their choice than on ours. I am always impressed by the affection and admiration people develop for their priests. But when you scratch the surface you come up with the same pattern of human reactions from the priest as from any married couple. There is youthful enthusiasm, at times over the top, there are strains on family and domestic relationships, there are bereavements, sometimes sudden always traumatic, there are precious moments of affirmation from close friends and colleagues, the better for being unpredictable and unexpected. There is, at least for me personally, a deep and unfailing sense of security in the mystery we call faith. I think Dante has given us the best definition of the arena of faith. He called his masterpiece the Divine Comedy.

I hope I have made the point that it’s normal to be a priest, or to want to be a priest. I would be worried if, as a believing Christian, you considered me any less human, any less marked by human experience than any of yourselves.

Jesus comes up with two strong metaphors in the Gospel we have just heard. He says You are the salt of the earth. You are the light of the world.

These metaphors apply to you as much as to me. They apply to all disciples of the Lord. Before my call to be a priest, I am called to be a disciple. Each one of you is also a disciple, a pupil at the school of the Master, taking time out to learn, aware of the privilege, happy to have achieved what you have, always keen to learn more. You will understand that if my examples of discipleship are from my own experience, it’s not because they are more valuable than yours; it’s because of the personal nature of this celebration.

You are the salt of the earth. Earlier this month I met up with my former classmates in Maynooth where we were ordained together by the late Archbishop McQuaid on this day, fifty years ago, 22 June 1958. Of the 61 ordained on that day, 25 turned up for the re-union, in varying degrees of general health and mobility. Most of the absentees had gone to their reward, others were too ill to travel, others are overseas and couldn’t make it. When you meet people you have not seen for fifty years, it’s a strange experience. The past comes alive again, the old characters are recalled, you enter briefly into another world, where much has changed and yet enough remains to be recognisable.

Maynooth in my time was like a large enclosed village. There were 600 students, preparing to be priests, and then about another 100 between professorial, maintenance and ancillary staff. Maynooth was, and still is, a national seminary with double university status, Pontifical and NUI. There was an intensive meeting of minds from all parts of the country; getting used to the accents initially took some time. There was the developing of common interests and ideas quite apart from our professional studies and spiritual exercises. Personally, I learned to value and enjoy the Irish language during my time there, due mainly to a charismatic professor of Irish who was convinced of the essential link between the pre-Viking pre-Norman Celtic or Gaelic tradition and the survival of the Catholic Church in the modern era. Even then it sounded rather romantic and far-fetched but it’s still an interesting thesis, fifty years later. Competitive sport was a big part of recreational life, as it still is in third-level colleges. It always fascinated me how Maynooth men are still remembered by their fellow-students decades later more by their performance on the playing fields than by any other single factor. I think it’s because sport gave more exposure to the real person than class or other social activities. I say that as one who was more often on the sideline than on the pitch. Anyway, to make my point, I met many men of fine character and outstanding talent in Maynooth, truly the salt of the earth.

A few weeks ago I had another meeting of a different kind. About nine or ten boys from St Macartan’s came with their religion teacher to interview me about my vocation. They asked me all the usual questions; why did I become a priest, when did I first decide, how long does it take, should priests be free to get married, would I do it again etc?

I was very impressed by their honesty and willingness to listen, and, I may add, by their good manners and good sense. The problem for me in sessions of this sort is to be equally honest and at the same time to speak in language that makes sense to young people. I am always happy to assure people that I have managed my life so far to my satisfaction and to the best of my ability, that I have never regretted becoming a priest and hope to remain that way, that I am daily thankful to God for his kindness to me through people like yourselves. It’s not, of course, for me to judge whether or to what extent I have been a shining light to the world. But I remain convinced that’s my ambition, as it has to be yours as a disciple of Christ.

In the Gospel passage at this Mass the image of the light is not a stand-alone. It is supplemented by the mention of the lampstand. “No one lights a lamp to put it under a tub; they put it on the lampstand where it shines for everyone in the house.”

There’s a vital point here for all of us. The light is Christ shining through each of his followers. But the light needs the lampstand to enable the light to be seen. That lampstand is the Church. It’s the Church that sets off the light and allows the light to be effective.

I don’t have to tell you there’s an ongoing debate these days about the relative roles of priest and laity in the life of the Church. Some say the priest is too fearful of letting go, that he is reluctant to share the decision-making, that he cannot see himself functioning any other way. Others hold that where the priest does share, he is effectively sidelined as strong personalities among the pastoral council take over, or that he is still left with the responsibility while others make or fail to make the decisions.

These are only some of the arguments. You will have your own ideas. The debate is far from being resolved; and finding the balance will take time and experimentation. My own main concern is that it can obscure the more fundamental issue of the Church itself, the crucial and urgent need to appreciate and enter deeply into the mystery of the Church. I will leave you with one thought. If you think of the decline in vocations, in religious practice, in the esteem in which the Church is held today, you may be tempted to think that the show is over, that the Church is finished. If the Church were a commercial concern, the prospects would be gloomy indeed. The Church, however, is something very different. It is Christ’s work of salvation, continued in the community of people which he established to continue it., and which he constantly strengthens and fashions for the work. To be less than hope-filled about the future of the Church is to overlook God’s own active participation in its life and work.

In the theology of Maynooth in my time there was a heavily-emphasised principle: Facienti quod in se est, Deus non denegat gratiam. ‘God does not withhold his grace from the person who does what in him lies.’ God’s grace is and must always be the basis of our hope. Our task is to do what we can within the Church, secure in the conviction that God will work with us as we do so. We are not called to carry the Church on our shoulders; Christ has reserved that role to himself, promising to be with his Church always and to ensure that it does not fail. The last words from a great Irish saint, Colum Cille of Iona, were from the psalm.

‘Those who seek the Lord will lack no blessing’.

end